Tube domain

In mathematics, a tube domain is a generalization of the notion of a vertical strip (or half-plane) in the complex plane to several complex variables. A strip can be thought of as the collection of complex numbers whose real part lie in a given subset of the real line and whose imaginary part is unconstrained; likewise, a tube is the set of complex vectors whose real part is in some given collection of real vectors, and whose imaginary part is unconstrained.

Tube domains are domains of the Laplace transform of a function of several real variables (see multidimensional Laplace transform). Hardy spaces on tubes can be defined in a manner in which a version of the Paley–Wiener theorem from one variable continues to hold, and characterizes the elements of Hardy spaces as the Laplace transforms of functions with appropriate integrability properties. Tubes over convex sets are domains of holomorphy. The Hardy spaces on tubes over convex cones have an especially rich structure, so that precise results are known concerning the boundary values of Hp functions. In mathematical physics, the future tube is the tube domain associated to the interior of the past null cone in Minkowski space, and has applications in relativity theory and quantum gravity.[1] Certain tubes over cones support a Bergman metric in terms of which they become bounded symmetric domains. One of these is the Siegel half-space which is fundamental in arithmetic.

Contents |

Definition

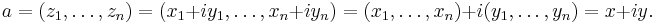

Let Rn denote real coordinate space of dimension n and Cn denote complex coordinate space. Then any element of Cn can be decomposed into real and imaginary parts:

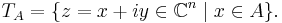

Let A be an open subset of Rn. The tube over A, denoted TA, is the subset of Cn consisting of all elements whose real parts lie in A:[2]

Tubes as domains of holomorphy

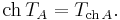

Suppose that A is a connected open set. Then any complex-valued function that is holomorphic in a tube TA can be extended uniquely to a holomorphic function on the convex hull of the tube ch TA,[3] which is also a tube, and in fact

Since any convex open set is a domain of holomorphy, a convex tube is also a domain of holomorphy. So the holomorphic envelope of any tube is equal to its convex hull.[4]

Hardy spaces

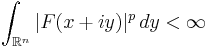

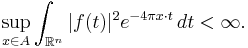

Let A be an open set in Rn. The Hardy space H p(TA) is the set of all holomorphic functions F in TA such that

for all x in A.

In the special case of p = 2, functions in H2(TA) can be characterized as follows.[5] Let ƒ be a complex-valued function on Rn satisfying

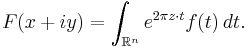

The Fourier–Laplace transform of ƒ is defined by

Then F is well-defined and belongs to H2(TA). Conversely, every element of H2(TA) has this form.

A corollary of this characterization is that H2(TA) contains a nonzero function if and only if A contains no straight line.

Tubes over cones

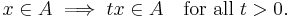

Let A be an open convex cone in Rn. This means that A is an open convex set such that, whenever x lies in A, so does the entire ray from the origin to x. Symbolically,

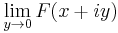

If A is a cone, then the elements of H2(TA) have L2 boundary limits in the sense that[6]

exists in L2(B). There is an analogous result for Hp(TA), but it requires additional regularity of the cone (specifically, the dual cone A* needs to have nonempty interior).

See also

Notes

- ^ Gibbons 2000

- ^ Hörmander 1990. Some conventions instead define a tube to be a domain such that the imaginary part lies in A; see Stein & Weiss 1971.

- ^ Hörmander 1990

- ^ Chirka 2001

- ^ Stein & Weiss 1971

- ^ Stein & Weiss 1971

References

- Gibbons, G.W. (2000), "Holography and the future tube", Classical and quantum gravity 17: 1071–1079.

- Lars, Hörmander (1990), Introduction to complex analysis in several variables, New York: North-Holland, ISBN 0-444-88446-7.

- Stein, Elias; Weiss, Guido (1971), Introduction to Fourier Analysis on Euclidean Spaces, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-08078-9.

- Chirka, E.M. (2001), "Tube domain", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://www.encyclopediaofmath.org/index.php?title=l/l057540